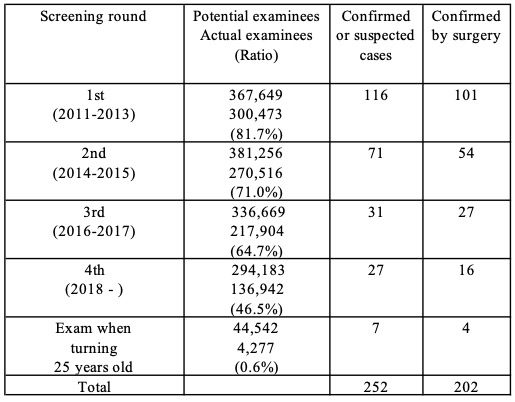

As part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey, regular thyroid exams are being conducted for persons who were 18 or younger at the time of the Fukushima nuclear accident, and among them, 252 have been diagnosed with or suspected of having malignant thyroid cancer, including 202 confirmed cases (from reports published by Fukushima Prefecture up to January 15, 2021). In addition, at least 19 persons underwent surgery or treatment for thyroid cancer at the Fukushima Medical University (as of February 2020). Persons identified in the Fukushima Health Management Survey as requiring follow-up observation were not counted in the survey totals if they were diagnosed later with thyroid cancer. It was announced that 257 persons (as of December 2018) who had thyroid exams in the Fukushima Health Management Survey were in a support program for patients with thyroid lumps (nodular lesions), but the details are not known publicly.

In any case, numbers are obviously missing from the officially announced statistics. Also, the results of surgeries are only being partially revealed. Clearly, many patients have lymph node metastasis and extrathyroidal invasion, and some have remote metastasis.

Children under 5 at time of accident also diagnosed with thyroid cancer

The Thyroid Examination Evaluation Subcommittee of the Fukushima Health Management Survey Review Committee stated that during the first screening cycle, “the number of detected cases was dozens of times higher than the number of thyroid cancer cases estimated by morbidity statistics,” but despite that it still concluded that “It is difficult to consider these to be impacts of the nuclear accident.” It stated reasons for this conclusion were that (1) the amount of exposure was lower than from the Chernobyl nuclear accident, (2) no cases were discovered among children who were under the age of five at the time of the accident, and (3) there are no big disparities in the rates of diagnosis in the region.

Regarding (2), it was later found that children under the age of five at the time of the accident were also diagnosed with thyroid cancer (among children aged four or five at the time of the accident). In January 2021, it was announced that girls who were below the age of one or were two years old at the time of the accident were diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Regarding (3), as described below, there were indeed regional disparities in the second round. As for (1), internal exposure to radioactive iodine was not being measured, so no comparison is possible.

The summary of the second round of screening stated the following opinion.

* The detection rate of thyroid cancer was slightly lower in the second compared to the first screening, but it was still tens of times higher than the morbidity rate estimated from patient statistics of thyroid cancer based on regionally registered cancer morbidity statistics.

* Regarding the detection rate of malignant or suspected cases, when compared simply without considering gender or age, it is highest, in rising order, in 13 municipalities in evacuation zones, Nakadori, Hamadori, and the Aizu region.

* No clear correlation was observed between radiation exposure and the rate of thyroid cancer detection as a result of using estimated thyroid absorption doses published by the UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR)

Data analysis expert Prof. Yutaka Hamaoka (Faculty of Business and Commerce, Keio University) commented that there is no gender difference by region, so even if adjusted for gender, the result would be the same. As for age, he said that the screening exams were done first in 13 municipalities that included evacuation areas, so the age there at the time of examination will have been younger. If adjusted for age, he said, the regional differences will become larger. Thus, it is not correct to say that regional disparities are due to gender and age differences. He also pointed out that analytical methods using UNSCEAR dosages result in reduced detection capacity due to the way they classify the subjects for analysis. There are also other factors that point to suspected links to the accident. For example, the observed 1:1 to 1:2 male-to-female ratio for thyroid cancer is higher than the typical ratio (1:7 to 1:8),[1] and the external radiation doses of people diagnosed with thyroid cancer are relatively high.

Source: Prepared by FoE Japan from Fukushima Prefecture reports up to January 15, 2021.

Lymph node metastasis, extrathyroidal invasion, relapses

Initially, the high detection numbers for thyroid cancer were attributed to the so-called “screening effect.”[2] However, detection at tens of times higher than normal in the first round of screening cannot be explained by the screening effect alone, and it does not explain the 71 cases of thyroid cancer detected or suspected in the second round, just two years later.

Some experts claim that the high incidence of thyroid cancer detection can be explained by “over-diagnosis” (cancer that does not have a life-threatening prognosis or is asymptomatic). However, Fukushima Medical University actually does conduct follow-up observations for minor and low-risk cancers. Prof. Shinichi Suzuki of that university performed surgeries and said that among 180 cases of thyroid cancer, 72% had lymph node metastasis and in 47% of cases it had spread to surrounding tissues, and surgery was necessary in all those cases.[3] He said that relapses occurred in 6% of the cases and required repeat surgery.

Support from the public

Since December 2016, the 3.11 Fund for Children with Thyroid Cancer (President: Hisako Sakiyama) has helped to cover the medical expenses of patients who live in Tokyo and 15 prefectures in eastern Japan, have thyroid cancer symptoms, and were under the age of 18 at the time of the accident. Up to the end of October 2020, the fund had supported 170 patients (110 from Fukushima Prefecture, 60 from elsewhere). The organization says that many cases of cancer being detected outside the prefecture were already at an advanced stage due to the lack of large-scale screening for thyroid cancer. Sakiyama commented, “Some [government] committee members were saying that screening at schools should stop, but people involved would actually like screening to be expanded and enhanced. For diagnosis, we should acknowledge that early detection and early treatment are succeeding.”

(Fukushima Today and Japan’s Energy Future 2021)

[1]The gender disparity in the male-to-female ratio for juvenile thyroid cancer at Noguchi Hospital, Ito Hospital, and Kuma Hospital was 1:7.7. Source: Presentation materials by Akira Yoshida (Kanagawa Prefectural Medical Association) at International Symposium by Fukushima Medical University, March 2, 2020. Thyroid cancer occurrence after the Chernobyl accident was also more common in males than for normal thyroid cancer.

[2]The “screening effect” is the higher number of detections of a disease as a result of mass screening, because more undiagnosed or pre-symptomatic diseases are discovered than when people go for diagnosis only after they notice symptoms.

[3]Second International Symposium of Radiation Medical Science Center for the Fukushima Health Management Survey, on February 3, 2020