Nuclear plant export dreams collapse

On the international scene, with the rapid growth of renewable energy, many countries are withdrawing from nuclear power. Going in the opposite direction, Japan has been promoting nuclear exports as a national policy, even after the nuclear accident in 2011. In response to the 2005 Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy under the (former) Koizumi Cabinet, a plan for national prosperity relying on nuclear energy was formulated the following year, featuring the Japanese nuclear industry. Until then the industry had been mainly domestic, but now it was seen as playing a leading role in promoting nuclear power in the international market.[1] A big effort was then made to sell to countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey, India and Vietnam. In 2016, after years of negotiations, a nuclear agreement was signed with India, and it entered into force in 2017 after a parliamentary debate.

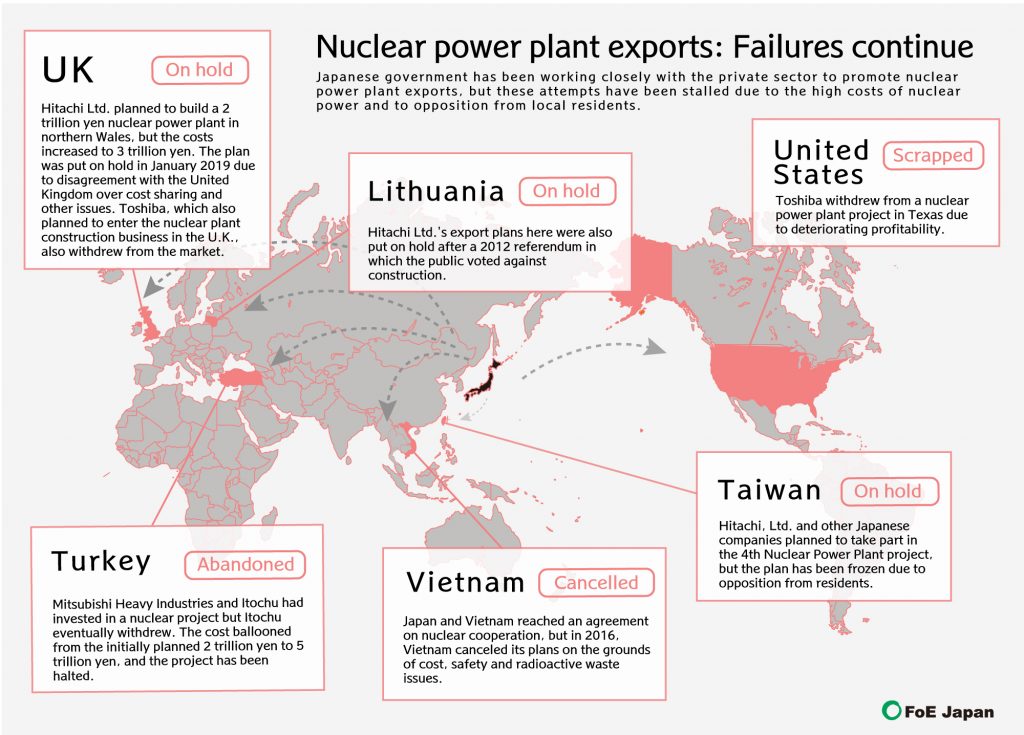

However, Japan’s concerted efforts for nuclear exports, reliant on generous helpings of public money, have ended in a series of failures due to ballooning costs and public opposition in other countries. Nuclear power has been exposed as the risky business it truly is.

Hitachi freezes nuclear plant export project in the UK

It was in that context that the Japanese manufacturer Hitachi, Ltd. was promoting the construction of a new nuclear power plant in the United Kingdom. Hitachi’s wholly-owned subsidiary, Horizon Nuclear Power Co., planned to build two nuclear generating units on the Isle of Anglesey in northern Wales. The local community spent years opposing the project due to concerns about the risk of accidents and impacts on the natural environment.

On January 17, 2019, Hitachi’s board of directors decided at an extraordinary meeting to freeze the project.

For a long time, Hitachi had stated there were three conditions to continue the project: (1) obtaining the necessary licenses and approvals, (2) assurance of profitability and (3) lowering Hitachi’s the investment ratio in the project and removing it from the consolidated financial results of the Hitachi parent company. The company eventually decided on the freeze because these conditions had not been met.

Proponents tried to shift 3 trillion yen in project cost risks onto Japanese and UK citizens

For Hitachi’s planned nuclear plant export, one big problem was who was going to cover the gargantuan three trillion yen in project costs. It was initially reported that UK and Japanese government agencies would directly invest in the project and provide government-backed loans. “The common understanding is that if the two governments do not have the commitment, the business cannot proceed,” said Hiroaki Nakanishi of Hitachi at one point (also chair of Keidanren, the Japan Business Federation). The concept was to shift the risks that could not be covered by one company over to the Japanese and British citizens.

To ensure the profitability of the project, Hitachi was asking the UK side to pay an expensive rate for the electricity that would be produced. Electricity market prices remain around 40 to 50 pounds per MWh. Meanwhile, the electricity rates from another nuclear power plant currently under construction in the UK are 92.5 pounds per MWh. Seeing the nuclear rates at about twice the market rate for other electricity, UK citizens loudly voiced their criticism.

Global exodus from nuclear power

It seems clear that the downward slide of the nuclear industry became more pronounced after TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in 2011.

As of January 2020, there were 447 operational nuclear power reactors worldwide and 52 under construction.[2] The ratio of nuclear to total electricity generation has been on a long-term downtrend since its peak at 17.5% in 1996, dropping to 10.3% in 2017.[3]

New solar (photovoltaic) installation in 2018 amounted to 165 GW (compared to 9 GW for nuclear). In 2018, wind power increased by 29%, solar by 3%, and nuclear by 2.4%. Over the past decade, the costs of solar power dropped by 88% (average generating cost)[4] and wind by 69%, while nuclear costs increased by 23%.[5]

Meanwhile, nuclear reactors around the world are aging. Excluding nuclear power reactors in long-term shutdown, the 413 operable nuclear reactors around the world had been operating an average of over 30 years in 2019. This included 80 that were already over 40 years old.[6]

In response to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, Japan set the operational service life of nuclear plants at 40 years in principle, although the numbers vary from country to country. In the U.S., the life is generally 40 years, but most are allowed a 20-year extension. However, even with extensions approved, decisions have been made to decommission several nuclear plants due to cost and safety concerns (e.g., Diablo Canyon, Vermont Yankee, and Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station).

As for Europe, nuclear power has been rejected as a result of public referendums in Austria, Italy and more. The governments in some countries such as Germany have adopted a national policy of nuclear phase out. Asia was said to have an active nuclear market, but it has been under pressure with construction delays, cancellations, and nuclear phase out policies.

In November 2016, Vietnam cancelled plans to construct nuclear plants, and in January 2017, Taiwan passed a law to abandon nuclear power. South Korea adopted a policy of phasing out nuclear power under the leadership of President Moon Jae-in. Indonesia has frozen nuclear projects and will not advance any until 2050 at the earliest. Both Thailand and Malaysia have postponed nuclear projects. Singapore eliminated nuclear from its energy options in 2012. China had plans to build 58 GW of nuclear capacity by 2020 but work is behind schedule. Incidentally, China already generates more electricity with wind power (366 TWh) than nuclear (277 TWh).[7]

Countries abandon nuclear power

1. Vietnam abandons pro-nuclear policy[8]

In November 2016, the Vietnam National Assembly passed a resolution calling for the cancellation of a planned nuclear plant construction in Ninh Thuan Province in the central-south part of the country. Russia was expected to receive the order for the first nuclear plant in that province, and Japan the second.

The main reason Vietnam decided to give up on nuclear power was that it made no economic sense. After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in 2011, projected construction costs for the nuclear plants rose from the initial projection of one trillion yen to 2.8 trillion yen, and projected electricity rates from nuclear power increased by a factor of about 1.6 compared to initial forecasts.[9]

Vietnam’s conclusion: “Nuclear power is not economically competitive.” For the construction of the plant from Japan, it had been agreed that Japan would provide preferential loans at low interest rates, and this most likely meant that government-affiliated financial institutions such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation would be involved. But the view that Vietnam should not increase its debt to Japan any further was another reason to cancel nuclear plans.

“This is a courageous withdrawal,” said Le Hong Tinh, Vice Chairman of the Committee of Science, Technology and Environment, in an interview with VnExpress. “The growth in electricity demand is slower than expected at the time the nuclear construction plan was proposed. Power saving technology has advanced, and LNG and renewable energy are starting to become competitive. We can adequately meet domestic demand. We need to stop the projects as soon as possible before suffering any further losses.”

2. Taiwan[10]

In January 2017, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan passed an amendment to its Electricity Act. The amendment states that the life of operating nuclear power plants will not be extended, and they will be decommissioned after they have reached 40 years of operation. This meant that Taiwan would no longer have nuclear power after 2025. Moreover, the amendment also stated that the renewable energy sector would be deregulated to promote private sector participation, and eventually to increase the proportion of renewable energy from 4% at the time to 20% by 2025.

In Taiwan, a strong civic movement demanding an end to nuclear power emerged after the lifting of martial law in 1987 and it shows no signs of losing momentum.

In 2018, the national policy of going nuclear free by 2025 was tested in a referendum, resulting in slightly more votes against versus in favor of nuclear phase out policies. However, among the four nuclear power sites in Taiwan, Units 1 and 2 were already past their deadlines to apply for an extension of operations, and the local mayor near Unit 3 is opposed to any extension. For Unit 4, a revised budget allocation would be needed to restart construction. In the referendum, although the “no” vote for nuclear phase out policy by 2025 won by a slight margin, the basic phase out policy has remained unchanged,[11] and in 2019, the Taiwanese government announced that there would be no change to the national nuclear phase out policy.[12]

3. Korea[13]

Twenty-four nuclear reactors were operating in South Korea, plus four under construction and six at the planning stage. Thirty percent of South Korea’s power generation came from nuclear. It was under such circumstances in 2017 that then-presidential candidate Moon Jae-in made election pledges regarding nuclear power (1) to stop construction of any reactors that were under construction, (2) to cancel any new ones being planned, (3) not to renew the licenses of operating reactors, and (4) to create a roadmap to exit from nuclear power in South Korea. But regarding new Kori Units 5 and 6, he said he “will reach a conclusion after hearing public opinion,” which was considered a retreat from his promise.

Public comments were accepted for three months starting in July 2017. A public debate committee was established, and it documented both the pro and con arguments for these nuclear projects. A first public opinion poll was conducted on 20,000 people, and considering region, gender and age, 500 among the respondents were selected as a group of citizens to participate. Among them, 471 studied up in advance, then participated in a comprehensive discussion and answered a final survey. The result was 40.5% voting for cancellation and 59.5% for restart of construction. Based on this result, the South Korean government decided to continue with construction of Kori Units 5 and 6. Besides the question about those two units, the participants were asked about the future of nuclear power. The results were 53.2% in favor of reducing nuclear power, 9.7% in favor of expanding, and 35.5% in favor of maintaining the status quo.

The design life of Kori Units 5 and 6 is sixty years, which translates into a significant delay in the ending of nuclear energy in South Korea. On the other hand, President Moon Jae-in said he would carry out the cancellation of all new nuclear power plant construction projects and the earliest possible deactivation of Wolseong Nuclear Power Plant Unit 1. Even before it reaches its planned service life, if that reactor is confirmed to be unnecessary for the electricity supply, that will be used as a basis to take policy steps towards its decommissioning.[14]

[1] Yoichi Nakano, Sekai no genpatsu sangyo to Nihon no genpatsu yushutsu (The global nuclear industry and Japanese nuclear exports), 2015.

[2] International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Power Reactor Information System (PRIS), accessed February 7, 2020.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Total costs including construction, operation and maintenance, divided by total power generated from operation to final decommissioning.

[5] World Nuclear Industry Report 2019.

[6] World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2019, Schneider et. al.

[7] World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2019, Schneider et. al.

[8] MITSUTA Kanna, “The global tide of the end of the nuclear era: Countries withdraw from nuclear, but Japan still clings on” Imidas (January 5, 2018) in Japanese.

[9] VnExpress, “Majority of legislators approve halt of nuclear plans,” 10-Nov-2016.

[10] “Taiwan: People Power Victory to End Nuclear Power” (FoE Japan, Sep. 2017, in Japanese).

[11] FoE Japan, Taiwan no datsugenpatsu ni matta!? Datsugenpatsu seisaku no yukue (Nuclear phase out in

Taiwan: Wait a minute!? The direction of nuclear policies) https://foejapan.wordpress.com/2019/01/28/taiwan-2/

[12] 31-Jan-2019, Mainichi Shimbun, Taiwan, datsugenpatsu hoshin wo keizoku, min’i mushi no hanpatsu

mo (Taiwan, some opposition to ignoring public will and continuing with nuclear phase out policy).

[13] FoE Japan, Kankoku: Datsu genpatsu wo motomeru hitobito no chikara (South Korea: People

power demanding an end to nuclear power) Feb. 2018. http://www.foejapan.org/energy/world/180206.html

[14] Hankyoreh (online) “Nuclear phase out roadmap expected to include decommissioning of Wolseong Unit 1,” July 22, 2017 (in Korean).